In 1943, Dr Harry Richardson, Principal of the Bradford Technical College, sensed an opportunity. Since his appointment as Principal in 1920, Dr Richardson had persisted with the ongoing quest for university status for the College (see Object 49). However, by 1930, complete discouragement meant he had put the matter aside to await fresh developments.

Dr Harry Richardson with students at Bradford Technical College, from Frank Hill’s Lecture on “Careers in the Wool Industry” 1955 (Univ/HIL)

In 1943, the British government was thinking about plans for improving society once the Second World War was over. Education was key. The progress of the War had highlighted the need for “brains for industry”: a skilled and well educated workforce who could create and manage new technologies. This could not be supplied by the existing ramshackle educational system, which was radically overhauled in the resulting legislation, the Education Act of 1944.

Technical education was of particular concern. Colleges (like Bradford’s) had grown up to train workers in local industries but there was no central planning to enable the country to develop university level technological “brains”. In April 1944, the Education Minister (R.A. Butler) appointed a Special Committee, chaired by Lord Eustace Percy, “to consider the needs of higher technological education in England and Wales”.

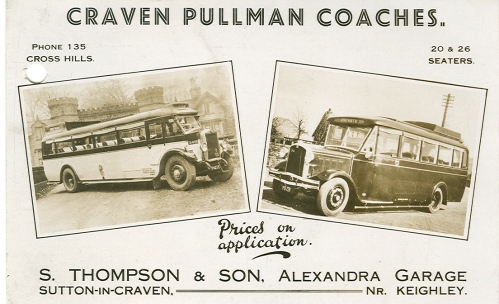

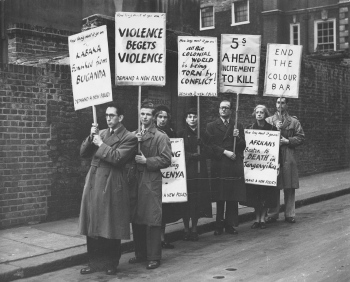

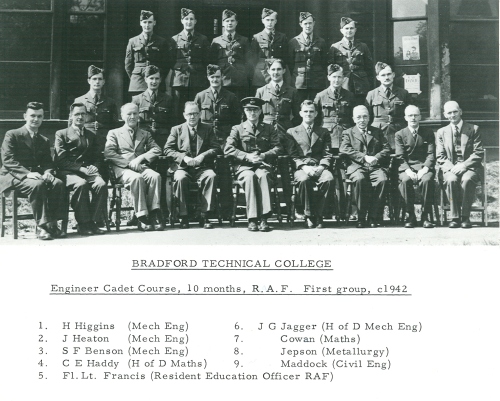

Bradford Technical College Engineer Cadet Course, 10 months, RAF, first group, c1942 (BTC 8/3) This illustrates how the College was supporting the war effort by providing training.

Harry Richardson was not just concerned with enhancing Bradford’s status. He understood the growing gap between the needs of industry and what technical colleges could offer while in local authority control. He argued the best way to improve technical education was for some such colleges to become university colleges, allowing them to specialise, develop their own curricula and form better links with industry.

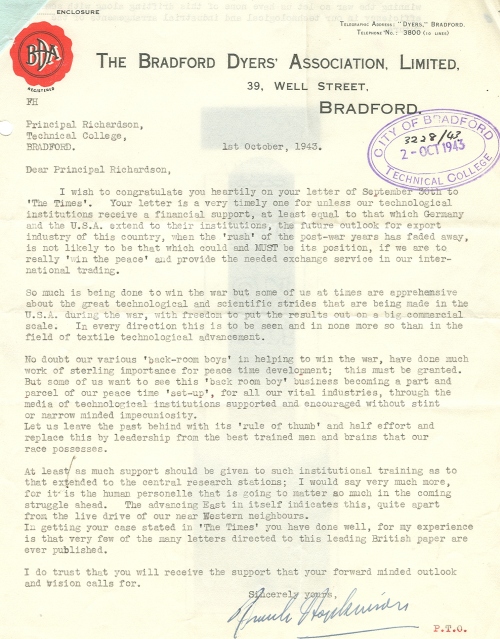

Special Collections holds Dr Richardson’s files of correspondence and press cuttings documenting his campaigning activity from 1943: writing memoranda and letters to newspapers and contacting key people (the Privy Council, the Ministry, the University Grants Committee, Percy Committee members, such as Dr Lowery of the South-West Essex Technical College). Crucially, he also nurtured support for his ideas among Bradford businessmen, councillors and the local newspapers.

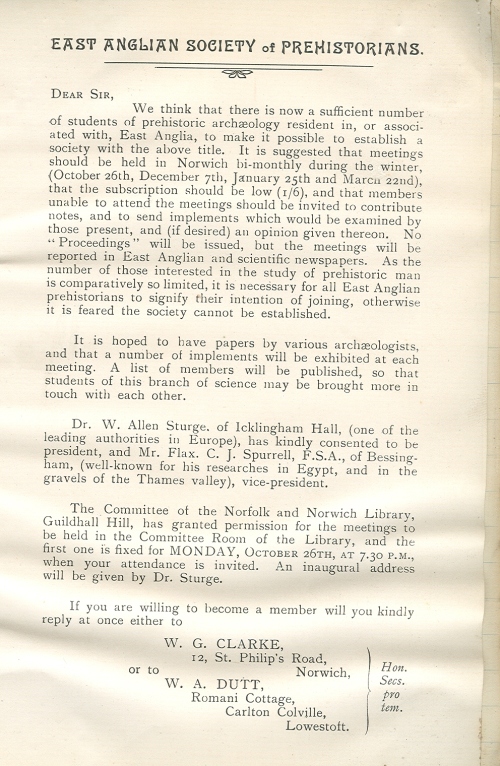

Letter from Hopkinson of the Bradford Dyers’ Association, 1 October 1943, praising Richardson’s recent letter to The Times newspaper and agreeing with the need for the country to invest in technological education (BTC 1/107)

The Percy Committee published its report, addressed to the new Minister of Education (Ellen Wilkinson), in 1945. Among its recommendations, the report called for the setting up of a limited number of technical colleges “in which there should be developed technological courses of a standard comparable with that of University degree courses”.

Ten years later, this proposal became reality: in 1956 following the publication of the White Paper on technical education, a small number of technical colleges which would “concentrate entirely on advanced studies” were designated. Bradford was one of these eight Colleges of Advanced Technology (CATs).

Percy had argued that advanced colleges would be more adaptable to industry needs if they were not set up as universities. In practice this caused problems for the CATs: they were universities in all other ways but lacked the power, autonomy and funding that the new “plateglass” universities had from the outset. The Robbins Committee addressed this concern, reporting in 1963 that the CATs should become “technological universities”; Bradford received its Charter in 1966.

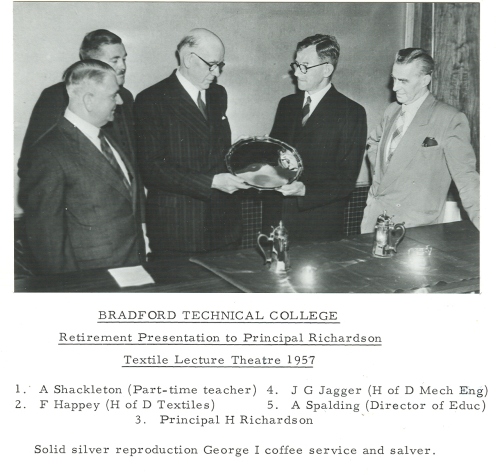

Retirement presentation to Principal Richardson, 1957, of a solid silver reproduction George I coffee service and salver. Richardson is the central figure (BTC 8/3),

Richardson retired shortly after the CATs were announced and died four months before the University came into being. He had played a vital role in these developments. He and his colleagues had maintained the high academic standards that were needed for the institution to be recognised as a CAT and his indefatigable lobbying maintained local support and ensured the city’s claim to a University could not be forgotten by those in power.

Sources: “Brains for industry” is a quotation from a Times Higher Education leading article of 10 November 1945 which endorsed Richardson’s call for technical colleges to become university colleges. McKinlay covers in detail the long and complicated story of Richardson’s campaigns and the development of technological universities.